Walsingham Publishing - King James Bible for CatholicsPublished on The Feast of St. Theodore of Canterbury, Bishop, 19 September 2020! A preview is available.

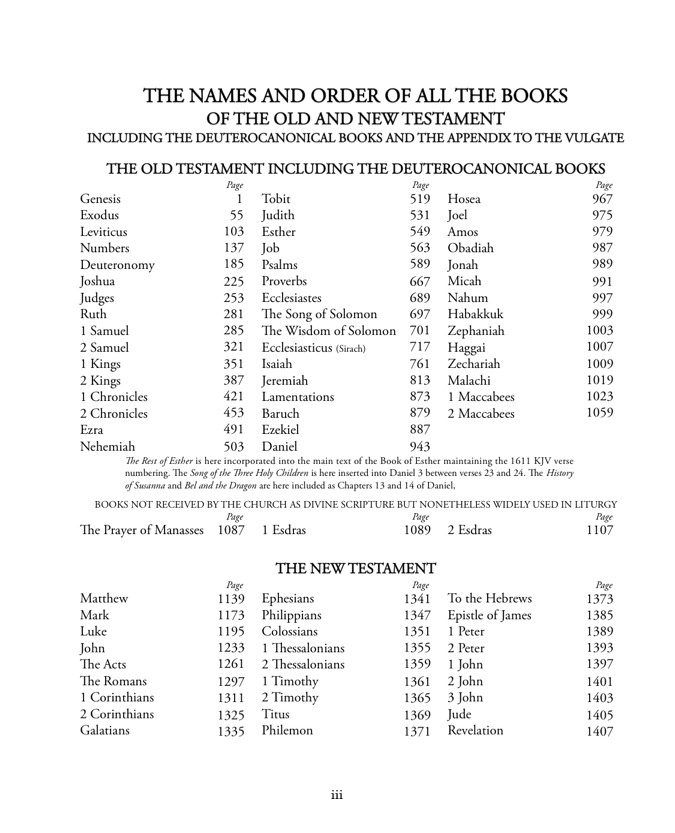

This is the full 1611 text of the Authorized Version of the most beloved and most published bible in the world. Designed for private devotional use by Catholics, all 80 books of the original 1611 edition are included. The 14 books not found in many later editions of the KJV have been included in the order Catholics expect within the 46 (not 39!) books of the Old Testament. As in the 1610 Douay, The Prayer of Manasses and the two additional Books of Esdras are placed in an Appendix. Then follow, of course, the 27 books of the New Testament. With an Introduction by The Rev'd David Ousley, Ph.D.

IntroductionWhy should Catholics be interested in the King James Version of the Bible? And why should there be enough Catholic interest to justify an edition of the KJV for Catholic readers? First, the KJV is good English. When the translators were working on it, they first translated as accurately and carefully as they could, working in small groups. Then they read the texts out loud to one another. This was a translation intended to be read in church, and the English needed to read well and be heard well. This was the age of Shakespeare, when good English was valued and practiced. No doubt the language of the Church or of the Court was not that of the street. But even those in the street still recognized that Church and Court demanded a more elevated idiom, and valued it. Understanding of this idiom does not seem to have been an issue: Shakespeare was popular with all classes. One result is that so many of the KJV’s memorable and felicitous translations have passed into the common heritage of the English language. The mote and the beam, “I will make you fishers of men,” “a man … shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh,” “Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.” Such examples are manifold. In this regard, the English of the KJV is generally superior to most modern translations. How much better is “In my Father’s house are many mansions” than “… many rooms.” Or Isaiah’s vision of the seraphim: “Each one had six wings; with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly.” Compare the Revised Standard Version: “… with two he covered his face, and with two he covered his feet, and with two he flew.” Of course, good English would not matter a great deal unless the translation were also accurate. The KJV is a good, honest translation. Unlike many of the early Reformation translations, it is careful to avoid polemics. It was intended to be unifying for all the Protestant Christians in England (the particular requirements of Catholics were not considered). It follows closely the Greek or Hebrew text. It is not “dynamic equivalence,” where the translator first decides what the text means and then renders his understanding of it in idiomatic English. That the KJV is instead a “literal” translation makes it useful for close study and as a basis for preaching. It is never a paraphrase and always bears close examination. The desire for accuracy extends to places where the original Greek or Hebrew is ambiguous. Most modern translations pick what they think is the most likely meaning. But so far as possible, the KJV prefers to convey the ambiguity. For example, “the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not” (John 1:5). “Comprehend” carries with it the sense of understanding (the powers of darkness didn’t get it), and also that the Light cannot be enclosed, limited, confined, and that the darkness cannot overcome the Light. The KJV does not choose one meaning, but conveys something of the richness of the Greek. The KJV uses “man” when that is what is in the text; it does not substitute “one” or use another generic circumlocution. Thus Psalm 1: “Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly … .” This allows us to see the Christological meaning which is obscured when the text is rendered, “Blessed are they …” as modern translations are apt to do. The use of the singular and plural personal pronouns (thee, thou, thy, ye) allows us to know whether the original is singular or plural – which the English “you” does not. While thee and thou may seem archaic, this is actually very helpful, since it helps us to be clear about whom the pronoun refers to. For example, when the serpent tempts Eve (Genesis 3), he says to her, “Ye shall not surely die … ye shall be as gods.” Ye is plural, so it is not just Eve as an individual who is being tempted, but Eve in essential union with Adam: mankind. Eve acknowledges this as she also uses the plural. Using “you” rather than “ye” leaves us in doubt as to whether it is about Eve alone or the whole of humanity that is entering into temptation. Accuracy is crucial in any translation, and few can rival the KJV. These are reasons that any Christian might benefit from the KJV. This edition of the KJV for Catholic readers is occasioned by the establishment of the Ordinariates by Pope Benedict’s Apostolic Constitution, Anglicanorum coetibus (2009). The Ordinariates provide a structure for Anglicans and Episcopalians desiring to enter the communion of the Catholic Church. The KJV has had a decisive influence on the character of Christian worship in the English-speaking world, and thus on the Ordinariates. For over 400 years, Anglicans and most English-speaking Protestants heard, read, marked, learned, and inwardly digested Scripture from the KJV. It was so well established among the faithful that when the modern translations began to appear, and were often favored by those in positions of power, the lay faithful often objected. The arguments advanced in favor of a more modern idiom, and that the KJV was no longer “vernacular,” carried little weight.1 Its elegant and accurate cadences formed the hearts and minds of the Christian people, especially Anglicans. Along with the Book of Common Prayer, the KJV formed the vernacular in worship and prayer. Long before the Second Vatican Council endorsed the principle of using the vernacular in the liturgy, the vernacular of the BCP and KJV was well established among Anglicans, and is a key element of the Patrimony which the Ordinariates bring into the communion of the Catholic Church. The language forms our prayer and liturgical language. Although Divine Worship: The Missal has included texts from the KJV, the KJV as a whole has not been authorized for liturgical use. Anglicanorum coetibus recognizes that the Ordinariates bring particular gifts to the Catholic Church, and our experience with this liturgical vernacular is surely one of them. The majority of those who have entered the Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter were using the Book of Common Prayer and KJV before entering the Catholic Church. Such is now recognized as a key part of the Anglican formation which has led to communion with the Catholic Church. Interestingly, the liturgical reforms under Pope Paul VI led some Anglican liturgists to abandon the heritage of the BCP and KJV and adopt the language of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite, feeling that this alone was “Catholic.” We are grateful that the Church has now affirmed the value of the traditional language, and sees that the Catholic Church can be enriched by it. This is historically fitting, since King James commissioned the translation to be used by all the Protestants in England. His ecumenical intent is now extended with this edition, making the KJV accessible to Catholics as well. A few words are in order about this edition. This is a new printing of the full text of the 1611 KJV Bible with the 1769 orthographic changes, and substitutions for eight occurrences of an Anglicization of the Tetragrammaton, as explained in the Note on page iv. It is offered for the private use of Catholics. The books of the Old Testament have been restored to the order familiar to most English-speaking Catholics. Details are given in the Note on page viii. The original KJV separated the books which were not thought to be part of the Hebrew canon and included them as “Apocrypha” between the Old and New Testaments. Most contemporary printings of the KJV omit them entirely. These books (and the sections of Esther and Daniel) are now returned to their previous places in the Old Testament, as in the Vulgate. This will make it easier for Catholics to find their way around, especially should they be using this with the Ordinariate Daily Office. The KJV has not been authorized for public worship in the Ordinariates, and thus this is not a “Catholic edition” of the KJV, but rather the KJV for Catholic readers. It is of course suitable for study, whether by individuals or in groups. It is hoped that this edition of the King James Bible for Catholics will enrich the lives of many Catholics, far beyond the Ordinariates. It is also offered to the Catholic Church as one element of the Patrimony which the Ordinariates seek to share with the Church according to the exhortation of Pope Benedict XVI in Anglicanorum coetibus. The Rev’d David Ousley, Ph.D. 1 The question of the priority of the modern critical texts of the Greek and Hebrew over the Received Text is beyond the scope of this introduction. Most modern translations are based on the critical texts while the KJV is based on the Received Text, which is still used in the Greek by the Orthodox Churches and the Eastern Catholic Churches. Note on the Old Testament CanonThe Hebrew Bible or TaNaKh consists of 24 books: the 5 books of the Pentateuch, the 4 books of the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings), the 3 books of the Latter Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel), a single book of the Twelve Minor Prophets (Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi) and the 11 books of the Writings (Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah, and Chronicles). In Western Christian bibles, these 24 books are divided into 39 books, with the Minor Prophets counted as 12 books, and Ezra, Nehemiah, I/II Samuel, I/II Kings, and I/II Chronicles counted individually. The Septuagint, the Greek Bible of the early Christians, included several additional books. Until the Council of Trent dogmatically affirmed in 1546 that the entire Latin Vulgate except for III and IV Esdras and the Prayer of Manasses enjoyed equal canonical status, there was no unanimity on the status of the books not included in the Hebrew Bible. When Saint Jerome translated the Greek and Hebrew bibles into Latin, he identified (a) “canonical books” recognized by the Jews, (b) “those that are read by Christians only,” and (c) “apocryphal books” rejected by Jews and Christians alike. Saint Augustine corresponded with Jerome between A.D. 394 and 405, with Augustine expressing reservations about use of the Hebrew text rather than exclusive reliance on the Greek. With respect to the canon, Augustine’s preference for the Septuagint prevailed, and all of the books Jerome had not listed as “Apocryphal” remained in the Vulgate. The legacy of Jerome’s opinion was long-lasting, most evident in the need for the Council of Trent to finalize the canon. Jerome’s placement of the Greek Additions to Esther at the end of the Hebrew text resulted in confusing verse and chapter numbering. This is clarified in the table of verse correspondences on the final page of the Book of Esther in this edition. Following Jerome, the original 1611 King James Bible placed the books not in the Hebrew canon in a section between the Old and New Testaments called “The Apocrypha”, consisting of 14 books in the following order: I and II Esdras (called III and IV Esdras in the Vulgate and 1610 Douay), Tobit, Judith, The Rest of Esther (those portions which Jerome had removed from the body of Esther and placed at the end), The Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (or The Wisdom of Jesus the son of Sirach), Baruch, The Song of the Three Holy Children (68 verses following Daniel 3:23 in Catholic bibles including this edition of the KJV), The History of Susanna (Chapter 13 of Daniel), Bel and the Dragon (Chapter 14 of Daniel), The Prayer of Manasses, and I and II Maccabees. See the Table of Contents for the restored order of these books. As in the 1610 Douay, the 3 non-canonical books appear separately. This edition of the KJV has placed all of the Old Testament books in the order familiar to English-speaking Catholics. However, within the Catholic Church there is significant variation in the order of books. Catholic bibles not in English often use a different order. English-speaking Eastern Catholics use the Orthodox Study Bible, which includes additions used in the East. The Prayer of Manasses is placed at the end of II Chronicles. This is followed first by III Esdras, titled 1 Ezra, and then by the Book of Ezra used in the West, which is titled 2 Ezra. Nehemiah is next. The familiar books of 1 and 2 Maccabees are followed by 3 Maccabees, all following Esther rather than Malachi. The Book of Psalms includes a 151st Psalm. Isaiah through Daniel appear after, rather than before, the Minor Prophets, and there are several differences in order regarding the Deuterocanonical sections of Baruch and Daniel. Questions and answers.

Some specific portions of the KJV are approved for use at Mass. An example is shown on these missal pages below, along with the approval from Cardinal Sarah. No official KJV lectionary text is being considered as part of this project. Anything beyond publishing what is described on this page is Out-of-Scope at this time.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Preview of the KJV for Catholics.

John Covert, Acton, Massachusetts, USA